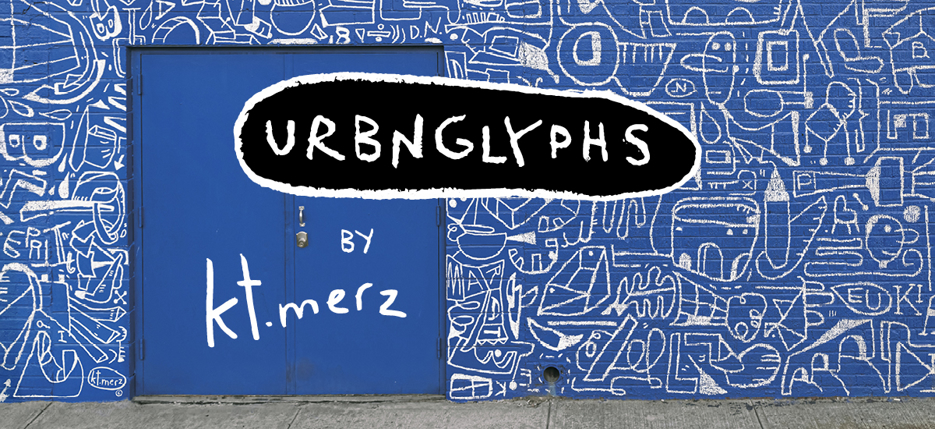

Life-long Brooklyn resident Katie Merz (“KT”) has become the most renowned street artist and contemporary muralist in New York. Her work translates the history, personality, and culture of neighborhoods and landmarks into hieroglyphs densely packed together in wild orientations, breathing new life and new perspectives into the city’s architecture.

KT shares her thoughts on bringing her work to a new environment through developing her debut mural collection with A-Street Prints:

When did you first fall in love with design?

Growing up in a house that my parents built had a huge effect on the way I intuitively understood balance and design. By living inside my parents’ minds, I was schooled in detail, subtlety and proportion. The scale and materiality of their house was so beautiful and simple, it took years for me to understand what they had actually done. I think physically understanding their space, instead of intellectually understanding it, was my slow and kinesthetic path to falling in love with the beauty of good design.

Did your parents’ careers as architects shape the medium you chose? Or was it your own relationship with the city, growing up in Brooklyn, that influenced your choices?

I think that actually watching them “practice” architecture had a huge impact on me. Their architectural office was on the top floor of our house, so I witnessed the whole process of building a building. This floored me. I noticed the value of a line - what it could do or mean and how it could indicate a built space. That process represented a magical translation and I wished myself to invent a kind of parallel magical language as well. Being a feral kid growing up in the 70s was also a huge influence on my work. Both aspects of growing up were a perfect convergence of the organized minds of my parents and the chaos and chance of playing on and in the streets.

Can you share more about the process of creating these pieces? Of how you translate and condense an area’s history down into its simplest and purest form? I make lists of words that have something to do the place I am working on. Then I draw a symbol for that word. It is like making emojis. I try to think really fast and not too hard about what the word looks like. I can make hundreds – it’s symbol notating but I always have to work from language. Language is the architecture. |  |

What motivated you to translate your works for the masses? To scale down and bring works that are intrinsically tied to a particular place somewhere new?

It was an accident. I was dared to tag a grain train in Nebraska while on an artist residency. I used an oil stick. It looked beautiful on the train’s black metal surfaces, so I tried drawing it on a few sheets of rough black roofing paper. I tacked that to the side of a barn and that was it. I saw language on architecture and that made total sense - after that it was full speed ahead. That was five years ago.

What’s the most exciting aspect of this collection for you?

The outside can go inside. And you can read up close what you won’t necessarily be able to read on the original installations. It brings the work into a room, into a private space but it is a wall - still an aspect of a public space and still working within an architecture. And it is not precious like a painting - it is holistic like an environment. This is all exciting to me: to stay on the wall but exist out of the frame.